|

A prototype

is any version of a video game produced before the final, released

game. In the case of a video game that was never commercially

sold ("unreleased"), any version of such a game is a

prototype.

A prototype

can go by several different names like sample,

dev cart, demo,

alpha,

beta,

pre-release, preview,

and review copy (among others).

There has been a lot of debate on what makes a prototype a prototype,

but just to reiterate, any version produced before the final game's

release is a prototype according to my definition. Alpha

refers to a considerably early build

(or version) of a game, whereas beta

refers to a game in a later stage of development nearing QA

(Quality Assurance,

i.e. bug testing) approval. I will go more into specific examples

of prototypes in the next section. For now, though, let's begin

by exploring why you should care about prototypes in the first

place.

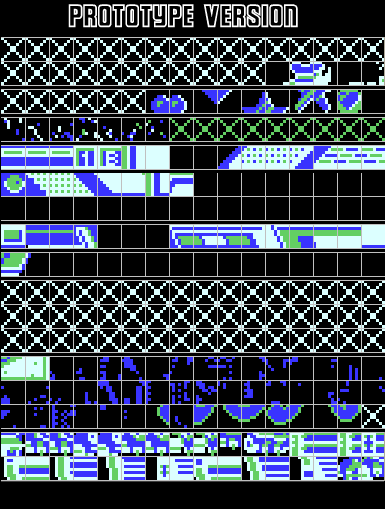

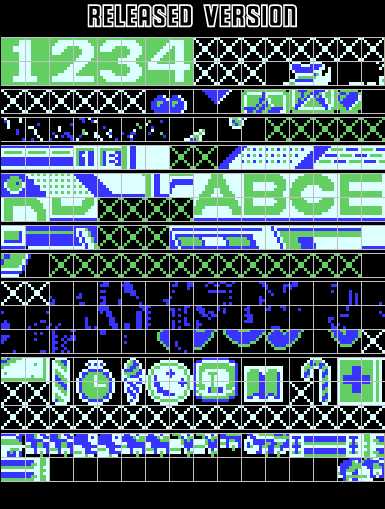

The greatest

allure of collecting a prototype of a released game is the possibility

of finding changes not seen in the final version.

These changes

could mean experiencing early or not-yet-developed graphics and

unpolished gameplay as in this Adventures

in the Magic Kingdom prototype. In this prototype, the

tile graphics on top of the Main Street, USA stores are not yet

drawn; the title screen is crossed out; several sprites in the

game are different or missing in cutscenes and such levels as

Space Mountain; and some buggy gameplay exists in the Big Thunder

Mountain Railroad level that can result in the train derailing

and entering a field of zeroes before crashing into an undeveloped

track.

At first glance,

an incomplete version of a game like Adventures in the Magic

Kingdom might not seem like much, but for someone like me,

who grew up playing this game for hours on end and whose memories

of visiting the Disney theme parks with my family remain a high

point in my life, having this unique opportunity to view the game

take shape is a very special thing, indeed.

And for anyone

who is interested in the process of game development: Nothing

beats putting a rough draft under a microscope, examining how

a game is formed over time, especially a title coming from a big

name company like Capcom.

Think of a

game that has always fascinated you. What if there were elements

removed or changed during the development of that game? How might

have things turned out differently? Imagine if you were able to

see how the game once was (or was meant to be). Now stop imagining

because answers to those questions could be hiding in a prototype,

just waiting to be found.

Playing a

prototype of a released game could also mean witnessing firsthand

something historically interesting like Nintendo's strict censorship

back in the day, as is seen in this Princess

Tomato in the Salad Kingdom prototype. In this version,

you can buy a clay pot, abbreviated as "POT," in stores

and choose to use it from the menu screen. The name of this item

was later changed in the final version to "VASE," presumably

because of the marijuana drug innuendo of buying and using pot.

If Nintendo made Hudson Soft change something as small and innocent

as a reference to a clay pot, imagine what other major game content

in the vast NES library might have been muffled and censored,

too.

In the case

of prototypes of games never before released, it isn't hard to

see why they are in such hot demand (and fetch much more money)—to

be able to finally play a game that has been stored away for decades is a dream of any NES player.

These are

only a few reasons why prototypes can be worth your time, money,

and effort. Now let's take a look inside of a prototype to see

how it functions.

Know

your EPROMs. Know

your EPROMs.

The plastic

Nintendo cartridges that we've all held in our hands act like

protective shells for the circuit boards inside. These circuit

boards are called PCBs (Printed

Circuit Boards). The data found inside of the majority of prototype

carts is stored on memory chips on the PCB called EPROMs.

"EPROM" stands for Erasable Programmable Read Only Memory.

Masked

ROMs... unmasked! Masked

ROMs... unmasked!

Game data

found inside of nearly all regular, officially licensed

Nintendo carts is stored not on EPROMs, but rather on memory chips

on the PCB called Mask ROMs

(or Masked ROMs/ROMs/MROMs).

"MROM" stands for Mask Read Only Memory. From this point

forward, Mask ROMs/Masked ROMs will be referred to as "MROMs"

to differentiate them from the term "ROMs," which people

confuse for ROM images, or

the files you can download and play on emulators.

If I'm starting

to lose you with all of the terminology, let's step back for a

moment with an analogy.

If you're

like me and enjoy burning CDs of your favorite music, think of

MROMs as a CD+/-R, and EPROMs, as a CD+/-RW.

If you ever

burned music before on a CD-R, you'll know that you're stuck with

whatever songs you chose to put on the disc after the files have

been copied. Even if later you have second thoughts about including

Rick Astley's "Together Forever" on your Ultimate Club

Mix track list, a CD-R can only be burned once—the music

files are permenantly stored on the CD—and no amount of pointing

out the irony of being stuck forever with "Together Forever"

will ever change that.

If, instead,

you opted to use a CD-RW to burn your music CD, you could have

avoided any future regrets by placing the disc right back into

your computer drive, removing Astley, and finding a better song.

(Might I suggest Milli Vanilli's "Ma Baker" as a worthy

substitute?)

EPROMs were

the way that game developers removed their "Astley mistakes"—they

gave developers the ability to test games still in development

on an actual Nintendo system, allowing them at any time to transfer

a newer or more complete version of the game for future bug testing.

This continual process of copying (i.e. burning), testing, erasing,

and re-copying data gave developers the means to update their

games and try them out for as many times as was needed without

having to throw away one-time use MROMs (the same way as you might

have thrown away countless CD-Rs before investing in a drive compatible

with CD-RW).

Unlike permanent

MROMs, EPROMs were never meant to last for a very long time—they

were temporary solutions for testing games or flashing them quickly

to ship them out to gaming publications for previews and reviews

before the mass-produced carts were manufactured.

Have

you covered up your EPROMs today? Have

you covered up your EPROMs today?

A sure way

of visually differentiating an EPROM from an MROM is by seeing

if there is a small square in the middle of the chip like the

one above. This is called an EPROM window,

and it's made of quartz crystal that makes it reflective like

a hologram. Exposing this window over time to a certain amount

of UV light (like the sun's rays) will gradually erase the game

data stored on an EPROM.

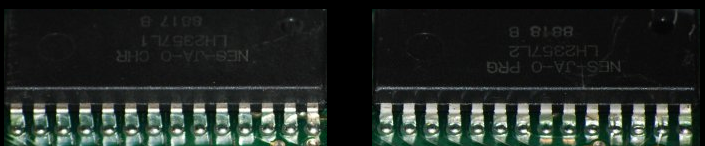

Official

Capcom sticker on an Adventures in the Magic Kingdom proto

EPROM. Official

Capcom sticker on an Adventures in the Magic Kingdom proto

EPROM.

To prevent

the game data from erasing, EPROMs on prototypes are often covered

with an adhesive sticker to

help block out UV light. Capcom, for example, had special company

stickers of their own made and placed over EPROM windows.

EPROMs can

also be erased over several years without any direct exposure

to UV light. Just how long it takes for the data to erase under

normal temperate conditions, without sunlight or other UV light

to progress the erasure, is a discussion that has gone on for

some time now. The slow erasing of data without exposing the EPROM

to UV light is what as known as bit rot,

and I will go more into that subject in a later section on why

it is important to dump prototypes.

EPROMs are

not unique to prototypes alone; they can be found on some other

games, as well. Several pirated

and unlicensed games, like all three of the Panesian

pornographic titles, use EPROMs. (This means that, one day, Panesian

collectors will be left with nothing but their own self shame.)

Test

carts are examples of official, non-prototype Nintendo games

using EPROMs. These were cartridges given to Nintendo Service

Centers to help diagnose console and accessory problems.

In rare cases,

there have even been reports of EPROMs being spotted in some officially

licensed and released Nintendo carts.

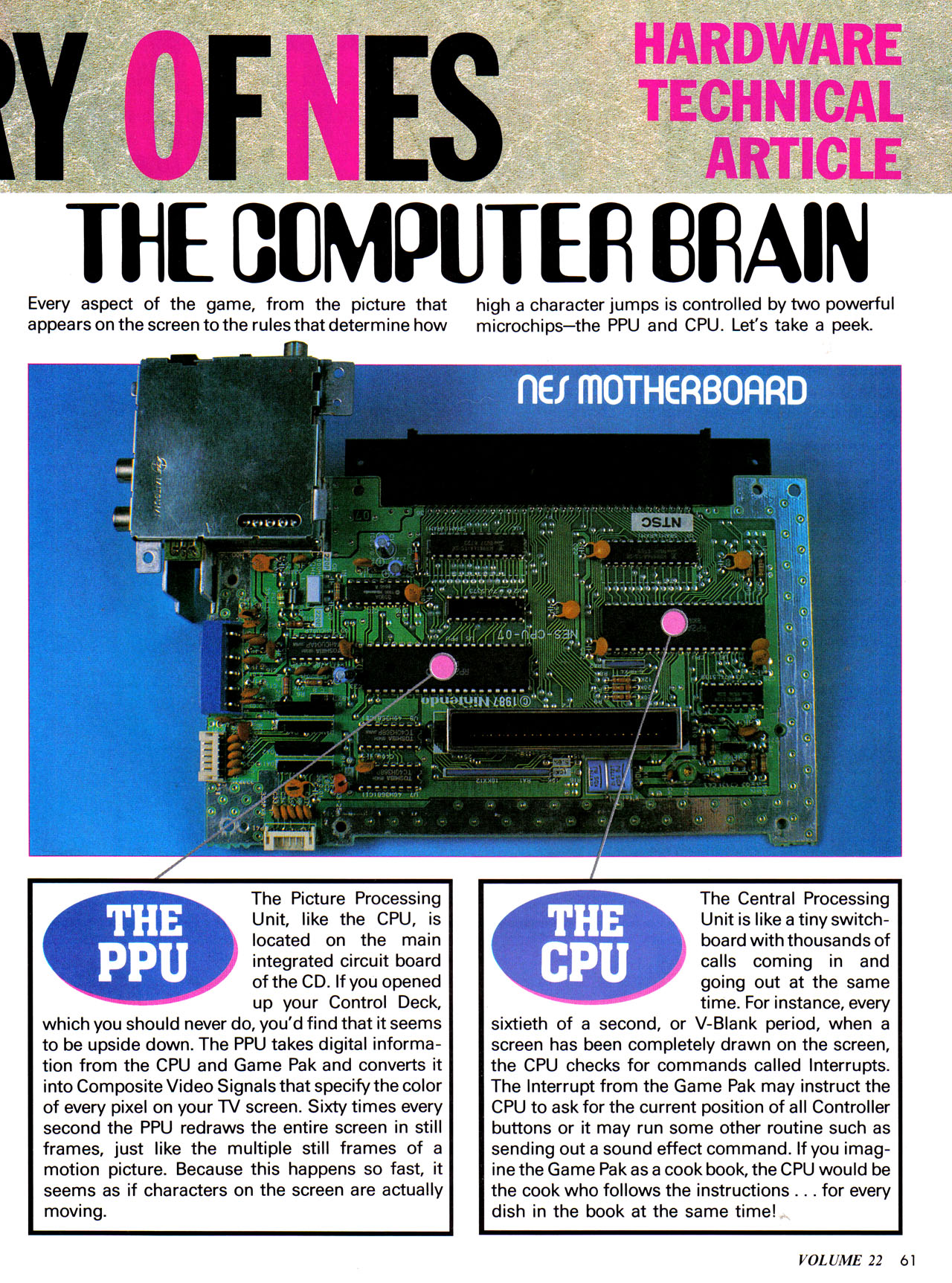

Nintendo

Power explains the PPU and the CPU with a cooking analogy. Nintendo

Power explains the PPU and the CPU with a cooking analogy.  (Image source: RetroMags.com) (Image source: RetroMags.com)

But back to

the subject of prototypes: An EPROM in a prototype is commonly

marked on the EPROM sticker to identify the chip as either PRG

or CHR.

PRG stands

for "program," and it's, well, the program behind a

game that can be read by an NES system's CPU

(Central Processing Unit).

CHR, on the

other hand, stands for "character," and it's where all

of the graphics in a game are stored to be read by an NES system's

PPU (Picture Processing Unit).

When combined,

they form like Voltron to give you the complete NES gaming experience.

(Note that, for some games, there might only be one EPROM inside

for the PRG, with the CHR being found on a RAM chip.)

I know all

of this is a lot to take in if you're new to prototypes. You may

wish to re-read this section again to make sure you have everything

down. When you're ready to continue, the next section covers how

to find and identify authentic NES prototypes.

|